As most of the Biblioverse knows, the Codex Climaci Rescriptus was purchased by Steven Green, owner of Hobby Lobby, and placed within a larger collection entitled Passages which is currently on the first leg of its tour in Oklahoma City.

I am not sure what I expected, but I thought perhaps I would see the codex highlighted and surrounded by a few other items shown on the Passages website. This was not the case. Whether by lack of marketing were whether by intentional understatement, the extent and quality of the collection is both surprising and overwhelming to the degree that the Codex Climaci Rescriptus is almost swallowed up.

The one weakness of this exhibit is that there was no master list of display items. Had this been available I think the collection would have made a bigger splash; not necessarily for you academic types, but moreso for local pastors and knowledgable lay people who are aware of manuscript, translation, and printing history but have seen historical items only as photos in textbooks or on the internet. It is wonderful to find a high resolution scan of an ancient codex, but it is another thing altogether to read words on the living page.

In the absence of an official exhibit list, I offer here my own incomplete and hastily written list of items on display at the Passages exhibit. Judge for yourself whether the Codex Climaci has found a worthy home. But be aware, my list represents only about a third of the actual exhibit...

|

| "Evanis" Gospel illumination |

- Circular menorah hewn from a single stone. Most likely used in the 2nd temple, according to the display.

- Multiple medieval Torah scrolls- Yemenite, Sephardic

- Dead Sea Scroll fragment (was not able to get detail, maybe later)

- Bodmer papyrus XXIV

- Evanis Gospels, Greek, c. 1000.( illuminated on parchment. One of the earliest and smallest examples of calligraphic minuscule.)

- Multiple Greek papyri- 2nd-5th centuries

- Codex Climaci Rescriptus- only two leaves on display, one showing the underlying Greek text (with a handwritten "5" in the corner), the other showing the CPA palimpsest (the rest of the Codex is stored off site, in the possession of the Green family).

| "St. Cecilia" Latin Bible |

- van Hattem Bible (Latin)

- St. Cecilia Bible (Latin)

- Several Vulgates from 1200s (handwritten margin notes in Latin visible :) )

- Greek parchment "Letter from Theon", 3rd cent.

- Coptic papyrus Psalms 112 (111 in Protestant/Masoretic reckoning), 4th cent.

- Khabouris Codex, (open to show the Acts of the Apostles, ch 3) 11th cent.

- Multiple medieval French and German Bibles & prayer books

- Rosebery Rolle Bible

- Anglo Saxon printed gospels 1573

- Conveyance document (transfer of property title), signed by John Wycliffe's brother Robert and including his seal. 1393

- 1454 Gutenberg "noble fragment" of Romans

The Anti-Christ and 15 Signs of the Doomsday - 1462 Gutenberg Bible printed by apprentice Peter Schöffer, 1 of 4 surviving copies.

- 1480 Latin Bible with papal seal, taken by Napoleon

- The Anti-Christ and 15 Signs of the Doomsday (Der Antichrist und die fünfzehn Zeichen). Block-book. Nuremberg: Hans Sporer, 1470. Only surviving copy.

- 1493 Nuremberg Chronicle

- 1470 edition of "Antiquity of Jews and the Jewish Wars" by Josephus (Latin)

- 1471 edition of "Postilla Litteralis super Bibliam" by Nicholas de Lyna

- 1476 Venetian edition of "Summa Contra Gentiles" by Thomas Acquinas

- "The Imitation of Christ" by Thomas a Kempis, 1st edition. c 1418.

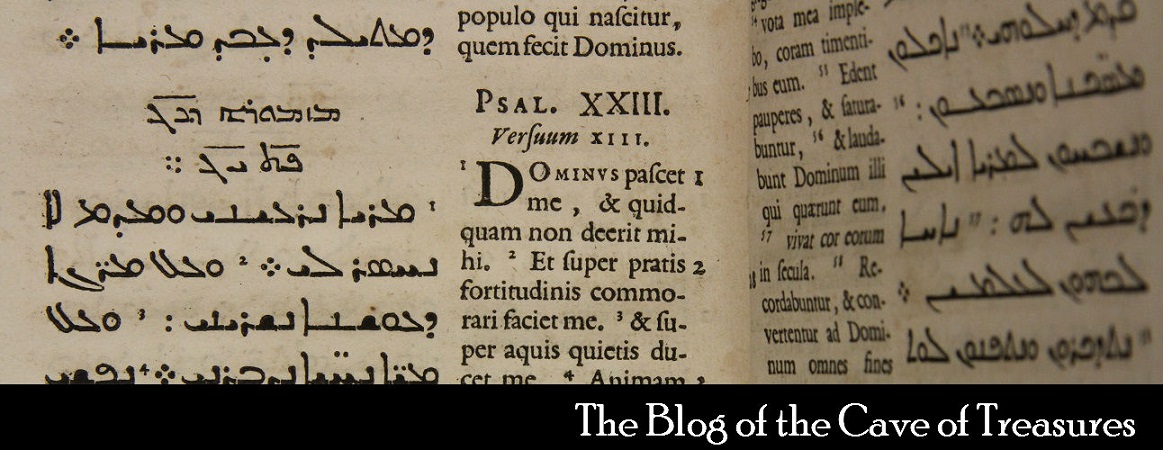

- Genoa Polyglot Psalms, 1516 (Greek, Aramaic, Hebrew, Latin, Arabic). Psalm 19 includes a margin reference to Christopher Columbus's voyage to the New World and the prophetic character the Gospel being carried around the world: Et in fines mundi verba eorum, Saltem teporibus nostris ... mirabili ausu Christophori Columbi genuensis, alter pene orbis repertus est christianoremus cetui aggregatus.

- Johannes Frobens "Poor Man's Bible" 1491 (Latin)

- Last Will and Testament, Martin Luther, Oct. 1518.

- "Babylonian Captivity of the Church" by Martin Luther, 1520.

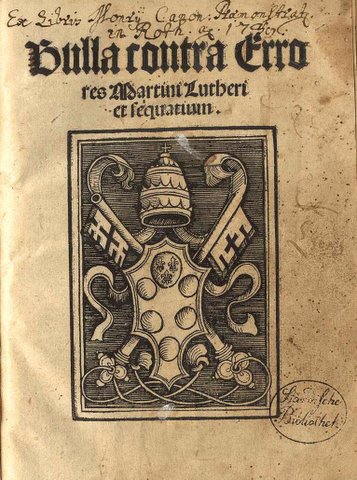

- Papal Bull Condemning Martin Luther, Pope Leo X, 1520.

- Papal Bull Condemning Martin Luther, Pope Adrian VI, 1523.

- a 1525 indulgence

- 1522 Erasmus' Commentary on his Latin paraphrase of the NT

- 1516 Erasmus Greek NT (the one that was rushed to print)

- 1521 Erasmus Greek NT

- Complutensian Polyglot, Vol IV, NT (whose typeface begat some of our modern Greek PC fonts)

- 1525 Daniel Bomberg Pentateuch (Hebrew text including Aramaic targum and Rabbinic commentary)

- Martin Luther NT 1524 illustrated/painted/gilded

- Tyndale Pentateuch 1530

- Tyndale NT 1536

- Coverdale Bible 1535

- Coverdale NT English/Latin 1538

- Taverner (Coverdale revision) 1539

- Geneva NT 1557

- Geneva Bible 1560

- "Bishop's Bible" 1568

- Rheims NT 1582

- 1611 1st edition KJV

- several KJV folio editions

- Stephanus Greek NT 1551

- multiple KJVs from 1600s

- "Wife Beater" Bible 1551

- "Child Killer" Bible 1795

- "Wicked Bible" 1631

- "Vinegar Bible" 1717

- multiple illustrated and engraved Bibles.

- 10th cent. Greek Psalter from Constantinople

- Psalterium Gallicannus Ferriatum (?) 1420

- Illustrated Psalter, Master of Jacques de Besancon 1480

- Speculum Humanae Salvationis, 1370, Tyrol

- Metal relief book cover by Salvador Dali for Sigmund Freud's Moïse et Monothéisme

|

| relief book cover by Salvador Dali (click on photo to enlarge) |