Judaism remembers the reclaiming of its most holy place and the miracle of the unfailing light at the temple's re-dedication. One day's supply of holy oil miraculously lasted eight days. Thus the Festival of Lights was born. While Christianity celebrates the same set of historic events on its ancient calendar, it has focused on the martyrdoms which preceded the temple's recapture, i.e. the ultimate sacrifice of those who refused to compromise the temple's sanctity. Judaism’s Hanukkah and the Christian veneration of the Holy Maccabeans are rare instances where the two religions (on different days of the year) memorialize the same martyrs.

The Old Testament book of II Maccabees recounts the story of the desecration of the Jewish temple around the year 165 BCE by the forces of Antiochus IV Epiphanes. Chapter six lists how the Greeks mobbed their way into the temple, interrupted, and overran the holy places:

For the temple was filled with debauchery and reveling by the Gentiles, who dallied with harlots and had intercourse with women within the sacred precincts, and besides brought in things for sacrifice that were unfit. The altar was covered with abominable offerings which were forbidden by the laws. A man could neither keep the sabbath, nor observe the feasts of his fathers, nor so much as confess himself to be a Jew. (II Maccabees 6:4-6)

The Greeks attempted to force the Jews to pay homage to the conquerors' religion and those who refused to comply were killed. As is common with political reformers, it didn't matter to the Greeks whether or not the Jews actually believed in the Hellenistic pantheon. What was important was that they made the religious opposition cry "Uncle". Chapter six continues:

On the monthly celebration of the king’s birthday, the Jews were taken, under bitter constraint, to partake of the sacrifices; and when the feast of Dionysus came, they were compelled to walk in the procession in honor of Dionysus, wearing wreaths of ivy. At the suggestion of Ptolemy a decree was issued to the neighboring Greek cities, that they should adopt the same policy toward the Jews and make them partake of the sacrifices, and should slay those who did not choose to change over to Greek customs. (II Maccabees 6:7-9)

The ancient Christian Church remembers the names of nine martyrs: Habim, Antonin, Guriah, Eleazar, Eusebon, Hadim, Marcellus, their mother Salomonia, and their venerable teacher Eleazar. The Jewish tradition on the other hand has passes down by name only one personality- the scribe and elder Eleazar. II Maccabees gives us a touching account of Eleazar's defiance:

Elea′zar, one of the scribes in high position, a man now advanced in age and of noble presence, was being forced to open his mouth to eat swine’s flesh. But he, welcoming death with honor rather than life with pollution, went up to the the rack of his own accord, spitting out the flesh, as men ought to go who have the courage to refuse things that it is not right to taste, even for the natural love of life.

"...by manfully giving up my life now, [says Eleazar] I will show myself worthy of my old age and leave to the young a noble example of how to die a good death willingly and nobly for the revered and holy laws.” When he had said this, he went at once to the rack. ...So in this way he died, leaving in his death an example of nobility and a memorial of courage, not only to the young but to the great body of his nation. (II Maccabees 6:18-31)

The martyrdoms of the seven brothers and their mother Solomonia are recounted in the next chapter. Eleazar's example then inspired a popular uprising led by by Judas Maccabeus. The temple was eventually retaken, ritually cleansed, and rededicated. Such a heroic event not only warranted its own holiday but also took on messianic significance. It was at this re-dedication that the miracle of the menorah light took place. We know that Christ himself participated in the "Hanakkuh" celebration of His time almost 200 years later:

It was the feast of the Dedication at Jerusalem; it was winter, and Jesus was walking in the temple, in the portico of Solomon... (John 10:22-23)(By the way, I think it is no coincidence that His "My sheep hear my voice" discussion occurs in the context of temple worship). Scholars have tried to unravel whether the martyrs’ shrines were located in churches or synagogues and on which religious calendar they were celebrated but in the process it became apparent that we are getting a glimpse into a shadowy and long lost the era when the boundaries between the two religions were more fluid.

The mother Salomonia becomes an even more important if cryptic figure when we take into account the various renditions of her name. It would be tempting to assume her name derives from the Jewish root word שלם SHLM meaning "peace", as in the case of the New Testament girl Salome. The late Semitics scholar Julian Obermann (1888–1956) helped tie together the variations of her name:

Catholic and Orthodox: Salomonia, Salomona, Salomonis, Samona

Syro-Aramaic: Shamuni, Shmuni

Rabbinical souces: Miryam, Hanna

Hebrew: Hashmonith

Obermann suggests her name is actually a reference to the Hasmonean dynasty in which she held a place of honor. Therefore within the Christian name of the mother lies hidden the Jewish dynasty of the times.

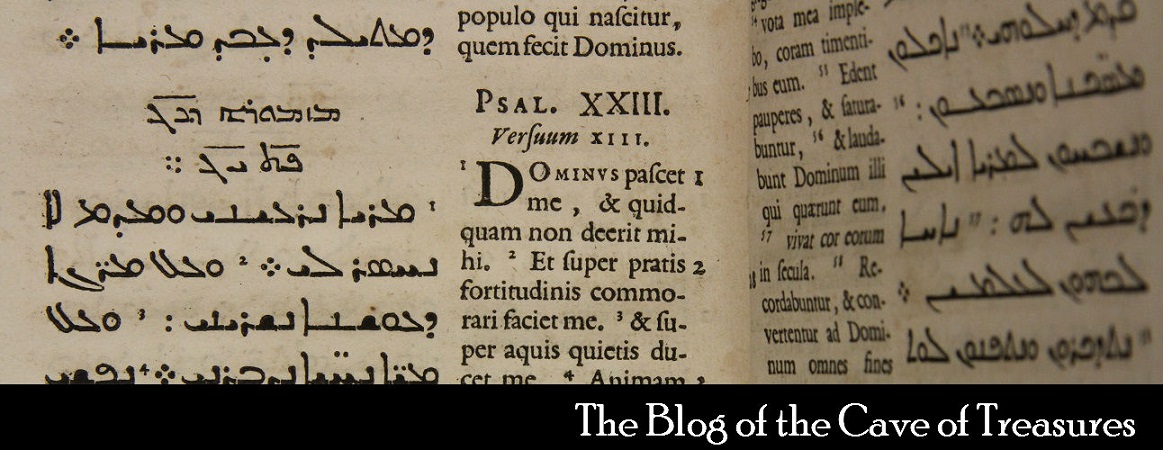

We know these martyrs continued to be venerated by the early Christians. The earliest proof of their veneration is from the mid-300s. Their feast day on the 1st of August is known as the "Festival of Shamuni and Her Sons" and is recorded in a Syro-Aramaic martyrology from the Antiochian Church:

bnai d'shmuni

"sons of Shamuni"

h'noon d'ktibin b'makabiyeh

"they who were written of in the Maccabees"

The Maccabean Martyrs are later given a place of high honor among the saints by Church Fathers Gregory of Nanzianus and John Chrystostom.

Out of all the Old Testament "righteous" people, why did the Church maintain a festival to the Maccabees alone in the same fashion as later Christian martyrs? This questions was posed to Bernard, the 12th century Abbot of Clairvaux. He wrote a touching response. He replies in part:

Therefore, though the motive makes martyrdom, yet the time and the nature of it determine the difference between martyrdoms. Thus the time in which they lived separates the Maccabees from the martyrs of the new law and joins them with those of the old; but the nature of their martyrdom associates them with the new and divides them from the old. From these causes come the differences of observance with which they are kept in memory in the Church. But that which is common to the whole company of the Saints before God is what the holy prophet declares: Precious in the sight of the Lord is the death of His saints (Ps. 116:15)Though the Christian focus is on the martyrs, the symbolism of light has not been lost. On August 1st the Orthodox Church still sings the following hymns (called Troparion and Kontakion) in memory of the Maccabean Martyrs

There are two things, as it seems to me, which make death precious, the life which precedes it and the cause for which it is endured; but more the cause than the life. But when both the cause and the life concur that is the most precious of all.

Let us praise the seven Maccabees,

with their mother Solomonia and their teacher Eleazar;

they were splendid in lawful contest

as guardians of the teachings of the Law.

Now as Christ’s holy martyrs they ceaselessly intercede for the world.

Seven pillars of the Wisdom of God

and seven lampstands of the divine Light,

all-wise Maccabees, greatest of the martyrs before the time of the martyrs,

with them ask the God of all to save those who honor you.

The "Seven" are the sons, remembered as children. Salomonia and Eleazar make nine- completing the total number of lights found on the menorah. A Christian icon of the Seven Maccabean Martyrs can be seen here:

http://www.uncutmountainsupply.com/proddetail.asp?prod=1MA02

Sources (I really don't care about formatting right now.):

- - Margaret Schatkin "The Maccabean Martyrs" Vigilae Christianae 28, 1974, pp. 97 - 113.

- - Julian Oberman "The Sepulchre of the Maccabean Martyrs" Journal of Biblical Literature, vol 50 No 4, 1931, pp.250 - 265.

- - William Wright "An Ancient Syrian Martyrology" The Journal of Sacred Literature vol 8 1866.

- - II Maccabees, Revised Standard Version Catholic Edition (RSVCE) http://www.biblegateway.com

- - Bernard of Clairvaux "LETTER XLIV: Concerning the Maccabees" Some Letters of Saint Bernard, Abbot of Clairvaux http://www.ccel.org/ccel/bernard/letters.xlvii.html

- - Thomas Purcell, Orthodox Menologion for Windows