Oklahoma

has been hiding one of its most interesting secrets for two years,

namely its very own Syriac scholar. Dr. Brent Landau, graduate of

Harvard Divinity School, is Assistant Professor at University of Oklahoma's Religious Studies Program.

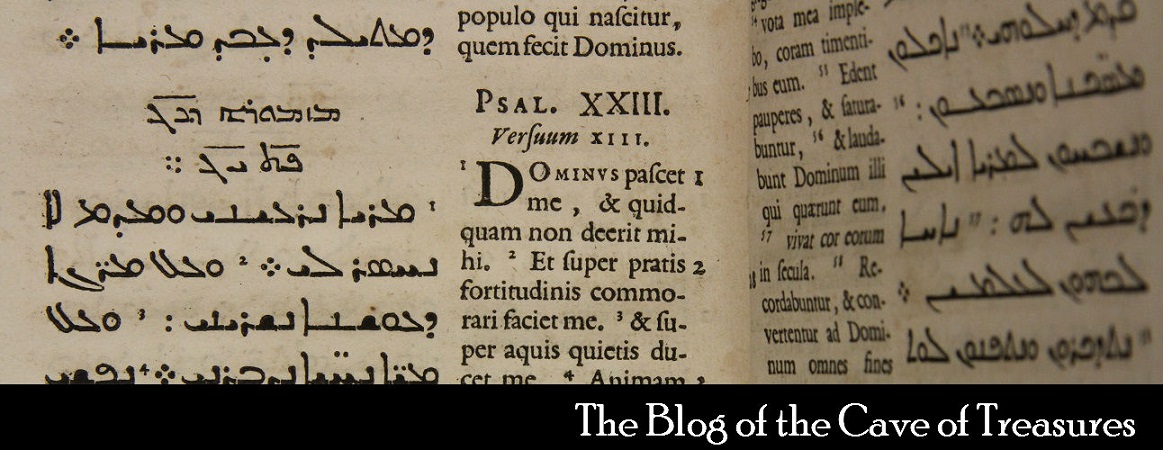

Dr. Landau is noted for providing the first English translation of what has been named the "Revelation of the Magi", a Christian apocryphal work and the most extensive Magi account from the ancient world. The Syriac narrative is preserved in a longer work comprising Vaticanus Syriacus 162, a codex housed in the Vatican Library.

Landau estimates the original "Revelation of the Magi" (ROM) was composed in the late second or early third century and was written from the perspective of the Magi themselves. It was then redacted in the third or fourth century to include the Apostle Thomas in a third-person account. The Vatican manuscript used by Landau for his English translation is from the 8th century.

With the Nativity approaching it is no accident that Harper Collins has released Landau's research entitled Revelation of the Magi: The Lost Tale of the Wise Men’s Journey to Bethlehem, based on his dissertation and edited for the wider audience in mind. The press releases and articles begin with the usual dramatic titles about lost scrolls and Christian origins. My favorite is...

.jpg) This

ancient text sheds light on an aspect of the Nativity often taken for

granted. Yet the ROM in no way stamps "solved" upon the story of the

Wise Men. Just the opposite, it (happily for bibliophiles) raises more

questions and suggests relationships with early Christian hymnody and

other sources.

This

ancient text sheds light on an aspect of the Nativity often taken for

granted. Yet the ROM in no way stamps "solved" upon the story of the

Wise Men. Just the opposite, it (happily for bibliophiles) raises more

questions and suggests relationships with early Christian hymnody and

other sources.

ROM is well-crafted and the narrative includes some intriguing points of interest such as; the Magi never refer to Christ by name, their food supplied by Providence appears to have hallucinogenic qualities (or at least that is how it might be described in modern terms), and the original author linguistically equates the Wise Men's title "Magi" with "silent prayer" in some unknown language.

Among the more surprising aspects is the notion that the star of Bethlehem followed by the Magi is far more than an astronomical event. Landau points out the star is actually the pre-existent Christ himself, "a literal representation of St. John's 'light of the world'”. The Johannine connection is certainly a strong one from our 21st century point of view. But when we also take into account the magi/silent prayer connection, the star-as-Christ motif seems to imply that the account is more than just legend and perhaps set within a larger theological context.

Landau recognizes within ROM similarities with Syriac baptismal hymns. I wonder if more light can be shed on these mysterious aspects if it were compared to other existing liturgical material. I cannot immediately recall if the Magi are mentioned in On the Mother of God by Jacob of Serug (trans. Mary Hansbury). If so, it might prove to be an interesting comparison.

If you are interested in seeing the Syriac text (nicely vocalized) and a more technical treatment of the ROM, Landau's dissertation can be downloaded here at Academia.com.

Dr. Landau is noted for providing the first English translation of what has been named the "Revelation of the Magi", a Christian apocryphal work and the most extensive Magi account from the ancient world. The Syriac narrative is preserved in a longer work comprising Vaticanus Syriacus 162, a codex housed in the Vatican Library.

Landau estimates the original "Revelation of the Magi" (ROM) was composed in the late second or early third century and was written from the perspective of the Magi themselves. It was then redacted in the third or fourth century to include the Apostle Thomas in a third-person account. The Vatican manuscript used by Landau for his English translation is from the 8th century.

With the Nativity approaching it is no accident that Harper Collins has released Landau's research entitled Revelation of the Magi: The Lost Tale of the Wise Men’s Journey to Bethlehem, based on his dissertation and edited for the wider audience in mind. The press releases and articles begin with the usual dramatic titles about lost scrolls and Christian origins. My favorite is...

.jpg) This

ancient text sheds light on an aspect of the Nativity often taken for

granted. Yet the ROM in no way stamps "solved" upon the story of the

Wise Men. Just the opposite, it (happily for bibliophiles) raises more

questions and suggests relationships with early Christian hymnody and

other sources.

This

ancient text sheds light on an aspect of the Nativity often taken for

granted. Yet the ROM in no way stamps "solved" upon the story of the

Wise Men. Just the opposite, it (happily for bibliophiles) raises more

questions and suggests relationships with early Christian hymnody and

other sources.ROM is well-crafted and the narrative includes some intriguing points of interest such as; the Magi never refer to Christ by name, their food supplied by Providence appears to have hallucinogenic qualities (or at least that is how it might be described in modern terms), and the original author linguistically equates the Wise Men's title "Magi" with "silent prayer" in some unknown language.

Among the more surprising aspects is the notion that the star of Bethlehem followed by the Magi is far more than an astronomical event. Landau points out the star is actually the pre-existent Christ himself, "a literal representation of St. John's 'light of the world'”. The Johannine connection is certainly a strong one from our 21st century point of view. But when we also take into account the magi/silent prayer connection, the star-as-Christ motif seems to imply that the account is more than just legend and perhaps set within a larger theological context.

Landau recognizes within ROM similarities with Syriac baptismal hymns. I wonder if more light can be shed on these mysterious aspects if it were compared to other existing liturgical material. I cannot immediately recall if the Magi are mentioned in On the Mother of God by Jacob of Serug (trans. Mary Hansbury). If so, it might prove to be an interesting comparison.

If you are interested in seeing the Syriac text (nicely vocalized) and a more technical treatment of the ROM, Landau's dissertation can be downloaded here at Academia.com.

A critical edition will be available to the scholarly community when Landau publishes the Syriac text as part of Brepol's Corpus Christianorum Series Apocryphorum.

What does ROM's complex portrayal of the Wise Men tell us about early Christianity or at least about the Nativity itself? The appearance of the star-Child to the Magi is a clear statement of Christ's ability to reveal Himself to whomever He chooses. In other words, evangelization by humans is not always a necessary endeavor. ROM suggests the possibility that this revelation may be "but one of potentially many instances in which Christ has appeared to the people of the world". Indeed this is supported by the Acts of the Apostles. Beyond this, Landau proposes a more universal message, that the "revelatory activity of Christ as the primal cause of humanity’s religious difference." In other words, Christ could reveal himself in the person of Buddha, Mohammed, or as any religious identity.

Even

with ROM's atypical treatment of Christ, the concept of a revelation

within other religions brought to mind the ancient and ubiquitous

"Christ Pantokrator" icon which, like all icons, communicated Christian

belief through visual imagery. Not necessarily a triumphalist symbol, Christ Pantokrator suggests

that the various religious traditions are echoes of the truth, and

Christ, with His unending love for all humankind will at any time

abruptly appear in time and space to anyone for the purpose of affirming His

identity, as opposed to equating it to all other iconic identities

within the world's religious milieu. A traditional perspective doesn't

necessitate that other religions are always antagonistic.

Even

with ROM's atypical treatment of Christ, the concept of a revelation

within other religions brought to mind the ancient and ubiquitous

"Christ Pantokrator" icon which, like all icons, communicated Christian

belief through visual imagery. Not necessarily a triumphalist symbol, Christ Pantokrator suggests

that the various religious traditions are echoes of the truth, and

Christ, with His unending love for all humankind will at any time

abruptly appear in time and space to anyone for the purpose of affirming His

identity, as opposed to equating it to all other iconic identities

within the world's religious milieu. A traditional perspective doesn't

necessitate that other religions are always antagonistic.Though the message of the Magi as presented by Brent Landau is more ecumenical than many traditional Christians would be comfortable with, he treats conservative Christian beliefs with great respect and sensitivity both on paper and in person. I hope Brent Landau's expertise will be valued and sought out in a state where Christianity is so predominant.

I generally do not purchase pop culture books written by biblical scholars. But in this case I made an exception and was happy to do so, and for several reasons: it is a work by a recognized Syriac scholar in Oklahoma (the only one) and as an Oklahoman, I am intensely proud of this. Secondly, one gets the impression that the full value of ROM is yet to be discovered. The real story of the Magi will continue to unfold.